Hi everyone, here is another excerpt from my book project centered on the classical stages of Christian transformation: The Threefold Way. This piece speaks to the beginnings of my Purgative Way experience, with an emphasis on training with Spiritual Practices. This post is a little longer than usual. I hope it’s helpful. I continue to work on the book and am making good progress. I look forward to sharing more details with you as the project evolves. As always, thanks for reading and I’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

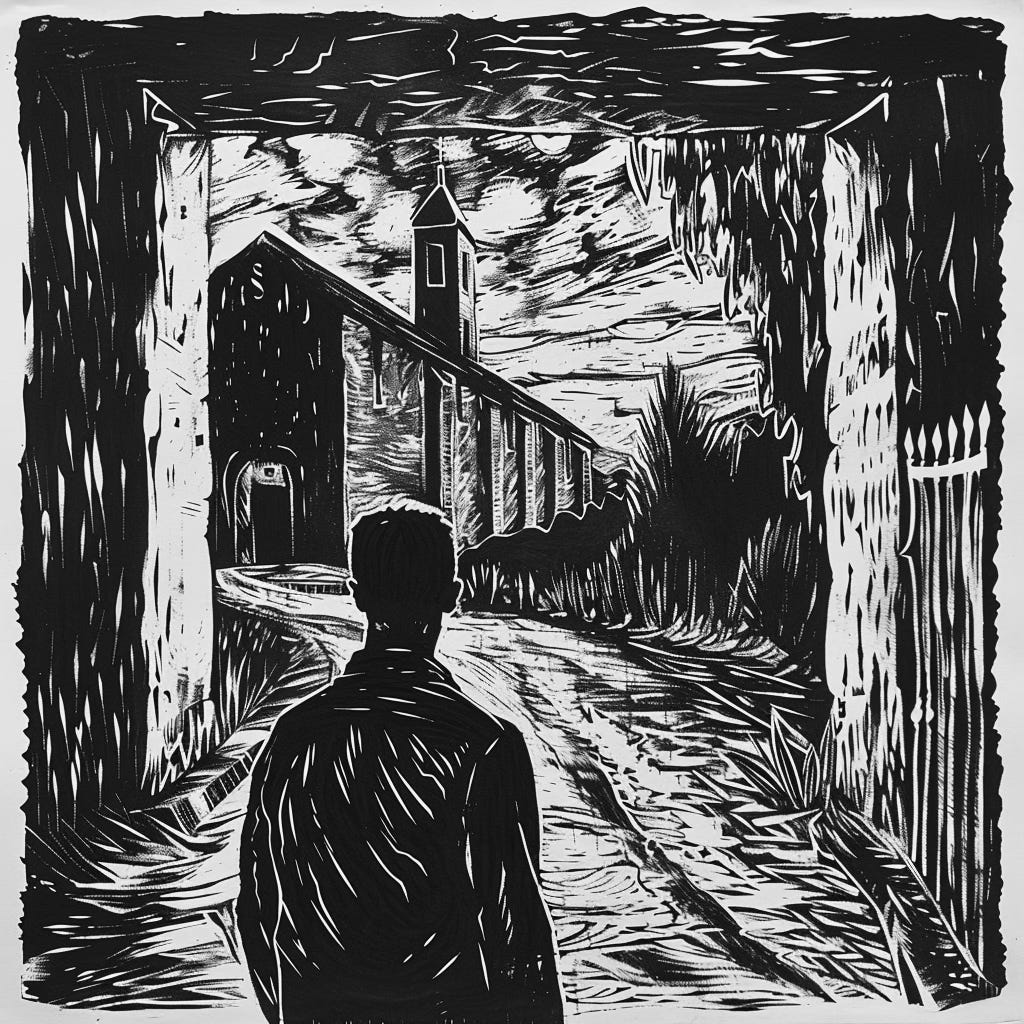

I remember not feeling the peace I was hoping to find but I walked forward anyway. In front of me, was a tall stone building with long grimy lines. The parking lot was empty.

I was alone.

Upon opening one of the wooden doors, a long, low-lit hallway revealed itself. Without a “Check-in Here” sign in sight, I tiptoed down the corridor, peeking into rooms.

After the third room, a dark haired woman appeared, “Can I help you?”

“Yes, Jonathan Bailey," I said, touching my chest.

“Right this way” she motioned.

"We don't normally do this," she said, easing herself into the cubby of her desk. “We’re more monastery than retreat center.”

Not an encouraging sign, I thought.

After finishing the paperwork, she drew a map to my room. I found it without much trouble.

The memory of the room is still vivid: There was a small writing desk butted against the wall with a table lamp for light. Caddy-cornered was an upholstered chair, a twin bed was against the wall. Everything in the room was dated and bare. And it didn’t bother me at all. I was drawn to the austerity, the simplicity; I liked the margins it made.

I had come to the monastery to try a new spiritual discipline I had recently read about.

This was my first silent retreat.

Death by Degree

After putting my things away, I decided to tour the monastery: I visited the library, the chapel, and the walking path on the back of the property.

All in silence.

All alone.

After a couple hours, I stepped back into my room, sat on the bed, and just stared at the wall. Hanging in front of me was a wooden crucifix. I’m not sure I’d ever seen one in-person. Growing up, my Evangelical tradition preferred bare crosses.

They were not comfortable displaying Jesus suspended on wood.

And maybe that absence had been starving me, starving me for one of the essential ways we participate in our transformation: asceticism, which is just a heavy, theological word for practicing spiritual disciplines of self-denial. Psychologists would probably call my longing a “deficiency need,” where the lack of a certain experience creates a craving or urgency for it.

I think that’s why I was at the monastery that weekend, to fill a hole, to satisfy a yearning, to perform a radical act of asceticism, a grand crucifixion—to orchestrate one magnificent death blow.

But being a novice, I didn’t understand the cross.

I thought of it, like a guillotine, with its tall frame and sharp blade.

The guillotine was designed to execute immediately; the cross was the polar opposite. It was designed to execute slowly, to prolong the process.

One of the earliest recorded uses of crucifixion occurred after Alexander the Great captured the island of Tyre. To instill submission from his new subjects, he ordered his men to fasten the surrendered soldiers to wooden stakes. Initially, they used rope, but when supplies ran low, they resorted to nailing the soldiers' limbs directly to the wood. Those bound by rope endured for several days, while those nailed to stakes died within 24 hours.

Regardless of how it was done, the purpose of crucifixion was to kill slowly and painfully, with an emphasis on humiliation.

This could not have been lost on Jesus when he invited his listeners to take up their crosses. Why use crucifixion as a metaphor? I can't think of a less persuasive way of inviting people into a life giving journey of transformation.

It’s hard to think of a worse metaphor.

It couldn’t have been that he just wanted to communicate that something inside us needed to die. There are less grisly ways to communicate that.

So, why crucifixion?

Maybe because he wanted us to know that learning self-denial is a long and painful process.

Vices can’t be beheaded. Transformation takes time. It hurts.

And we’re going to feel a little foolish as we go about it.

Hurrying Holiness

Back at the monastery, I remember wanting to escape.

And so I did.

I got in my car and took a break from the monastery.

This was my purgative pattern early on: I would jump into a spiritual practice, be unable to endure or maintain it—and abandon it.

For example, one of my first attempts at fasting was something like: No food for three days. I can’t recall if I achieved it. But that didn’t matter because the whole experience made me hesitant to fast again.

The problem was that I didn't think any of my actions were over-the-top—I thought they were normal.

I’d come across fasting in a book, maybe The Confessions or New Seeds of Contemplation or The Interior Castle, and then decide to implement it. What I failed to recognize at the time, was that what I read about in books was very often not meant for beginners. How Augustine or Teresa of Ávila or Thomas Merton fasted was not how I should begin fasting. All three were in the religious vocation, and deeply rooted in monasticism.

But it just seemed natural to put into practice what they were writing about.

Being a novice, I didn’t have a filter for how to transpose spiritual practices from someone further along the path to someone like me who was just beginning—let alone living out a different vocation in a different time and place.

And so this pattern kept repeating:

I remember being inspired by the Meditation chapter in Celebration of Discipline, and trying a full hour—but the ticking clock and my cramping legs made it too distracting to finish

I remember my friends and I spending months trying to help a homeless man escape street life—but the reality of his addiction and our limited capacity to help made it impossible

I remember trying to memorize the entire first letter of John—but the rigorous reading, writing, and quizzing made me give up before memorizing the first chapter

I failed at all of these practices, not because they weren’t attainable, but because I was aiming for heights that, at the time, were beyond me. They were too extreme, excessive, and severe.

Again, I kept trying to accelerate my crucifixion, trying to get it over with, speed it up. I was pursuing practices with intense dedication but very little wisdom. I was in a hurry for holiness.

And I guess that isn’t all that bad.

Who doesn’t want to finally break free from the vices that limit our love? Who doesn’t want to be permeated with God’s kind of gentleness, joy, and self-control? Who doesn’t want to shed the heaviness of self-centeredness for the lightness and freedom of other-centeredness?

Yes, those early days were a blessing and a curse.

I was getting involved with God—but I was going to extremes and none of it was sustainable.

It took years of practice before I finally recognized that training requires nurture, not force.

Becoming Spiritually Literate

After exiting the monastery grounds, I remember driving to another one of my sacred places, the bookstore. I liked this particular one because it had a coffee shop inside and I could do two of my favorite things at once:

Sip coffee and read books.

After grabbing my cup, I went straight for the Christian Living section. At the time, this is basically what spirituality meant for me. My Christian life was dominated by reading, by becoming spiritually literate. In fact, I felt most like a Christian when I was learning about it. I hadn’t understood what Thomas à Kempis recognized centuries earlier:

“Well-ordered learning is not to be belittled, for it is good and comes from God, but a clean conscience and a virtuous life are much better and more to be desired. Because some men study to have learning rather than to live well, they err many times, and bring forth little good fruit or none.”

That was me. I was erring and I didn’t even recognize it. I wanted learning. I wanted to know. I wanted to understand. My trap, however, lay in the assumption that simply gathering information would produce transformation.

But that wasn’t happening.

My library was expanding faster than my character was transforming.

But again, all of this is normal in the Purgative Way. I don’t beat myself up because of it. It’s simply part of the process. In the beginning, we over emphasize information acquisition because we’re trying to figure things out. We don’t have the benefit of lived experience, so we overcompensate by adding layer upon layer of information. This was my misstep. I needed to slow down consuming information and start practicing the information I had. As one of my favorite Spiritual Directors, François Fénelon, once wrote to one of his directees, “You already know much more than you practice. You don't need to learn new things nearly as much as you need to apply what you already have.”

Of course, I knew about spiritual practices:

Dallas Willard taught me that grace was not opposed to effort but worked with my effort. Richard Foster taught me to train instead of try to be like Christ. But what I hadn’t learned yet, was what practices to start with, how to implement them, and maybe most importantly how to maintain them. In other words, I didn’t know how to train with spiritual practices inside a Rule of Life, all of which emerged later, in the Illuminative Way.

Honestly, what I needed was in-person guidance from someone further along the path: a wise mentor, a Spiritual Director, or a contemplative Pastor, to use Eugene Peterson’s lovely phrase. I needed grounding in community, a rootedness in relationships.

Looping Fear

After an hour of thumbing through books, I grabbed some fast-food and recharged my enthusiasm.

When I returned to the monastery it was dark. I got to my room, turned the knob of the table lamp and tried reading through the entire letter to the Romans. I think Dallas Willard mentioned this on an old cassette tape once.

It was harder than I thought, so after the twelfth chapter I bowed out and went to bed.

The room got quiet—so quiet that I began hearing all the noises an old building makes. And that’s when the hysteria kicked in.

I remember staring at my door, wondering if someone would break through. It was locked, of course, but surely some sadistic monk had a key. I closed my eyes and tried falling asleep but the thought kept looping. I slipped out of bed and picked up the desk chair and angled it under the door knob. It probably wouldn’t stop someone from forcing their way in, but maybe it would give me a chance to prepare.

I laid down—more looping—the fear intensified with each iteration.

I couldn’t close my eyes without my imagination previewing the nightmare. I remember feeling overwhelmed. I remember not being able to take my eye off that brass knob.

Did it turn?

Was it turning?

I couldn’t do this.

I shot out of bed, stuffed my duffle bag, and eased open the door. I peeked down both sides of the hallway. It looked empty.

So, I ran—the library and chapel and Catholic statuary whizzing by.

Mercifully, the front door was unlocked.

I can still hear the gravel clicking furiously beneath my feet. I reached my car door with bag in hand. I threw the lock into place as soon as the door closed.

I was safe.

Confronting My Pseudo-Saint

Looking back on that experience, I see that I not only wanted to accelerate my crucifixion; I also wanted to be thought of as a spiritual hero.

Yes, there was a genuine longing to retreat into silence, but mixed in with all that clean, white longing was something less pure: I wanted to be noticed and admired.

I was experiencing my vice of Vainglory, which is common in the Purgative Way. “The flesh whines against service,” to quote Foster once more, “but screams against hidden service.” In other words, we like to advertise our spiritual accomplishments. Fortunately, I didn’t feel like sharing my first silent retreat. I arrived at the monastery a hero; I left humiliated.

Noticing all of this was both humbling and liberating. Humbling, because it forced me to confront an unflattering aspect of myself. Liberating, because with recognition came the possibility of an even deeper transformation.

Again, this is symptomatic of purgation. We all want the virtues right away, and what we get instead is a clearer picture of our vices.

For purgation brings illumination

Asceticism cultivates awareness

Detachment reveals disordered attachments

When we begin practicing spiritual disciplines, God begins our transformation by altering the way we perceive ourselves, gently correcting our self-deception. As this happens, we slowly trade illusions for reality, and the more we live in reality, the more transformation can occur.

“My library was expanding faster than my character was transforming.”

I’m humbled by these words! They ring so true - in my pursuit of transformation I’m so quick to think that metabolizing information is the path to get there. Lead on!

training requires nurture, not force.