Thomas Aquinas taught that goodness is primarily interested in how well something or someone perfects its purpose. Does it know its reason for being? And more importantly, can it achieve it?

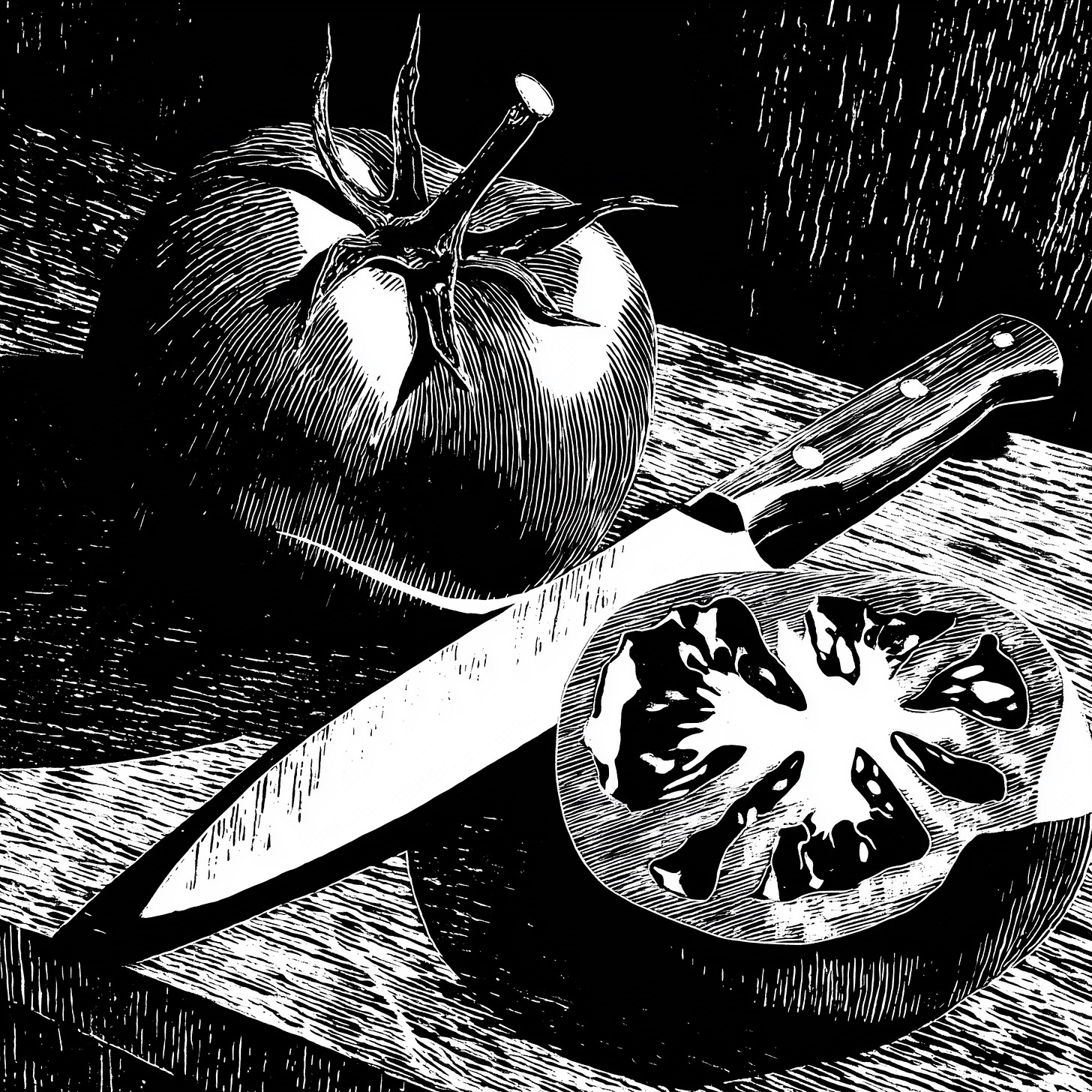

When I need tomato slices, I pull out an old paring knife and press hard on the stubborn blade. Instead of getting neat slices, I get tomato juice on my shoes! This is not a good knife. It is not fulfilling its purpose. For a knife to be good, it must be sharp.

“A thing is good,” wrote Aquinas, “to the degree that it perfects the powers appropriate to its nature.”1

In other words, it has the capacity to act, the power to deliver on its design. The power of the knife is its edge. The power of an artery is its openness. The power of a friendship is its loyalty. And the power of the human person is to grow with God, to make the divine goodness visible, to follow and find love—forever.

So when we talk about being made good, we’re not just talking about cultivating habits and attitudes of goodness as they are normally understood. We’re talking about something absolutely essential to our life and being; we’re talking about working with the Spirit to perfect our nature (Matt 5:48). And I’m not talking about the kind of first-century perfectionism that Jesus repeatedly opposed. I’m talking about the kind of perfection that is wholeness, order, and unity—the kind that by God’s grace and our wise effort enables us to regain our strength, our power, our glory.

Room to Reflect

Where do your gifts and the world’s needs meet — and how can you spend one hour there in the next seven days?

If Jesus opposed performative perfectionism, what would a gentler, purpose-driven excellence look like in your current season?

Can you identify which sphere needs sharpening most right now — mind, body, spirit, … relationships, or vocation? — and what is one small sharpening move you could make?

St Thomas Aquinas. Summa Theologica. (United States: Cosimo Classics, 2007), 23-30.