God wants to give us virtue, but he’s designed us with such terrifying dignity that we cannot receive—even good things—against our will.

As George MacDonald explains:

“Man finds it hard to get what he wants, because he does not want the best; God finds it hard to give, because He would give the best, and man will not take it.”1

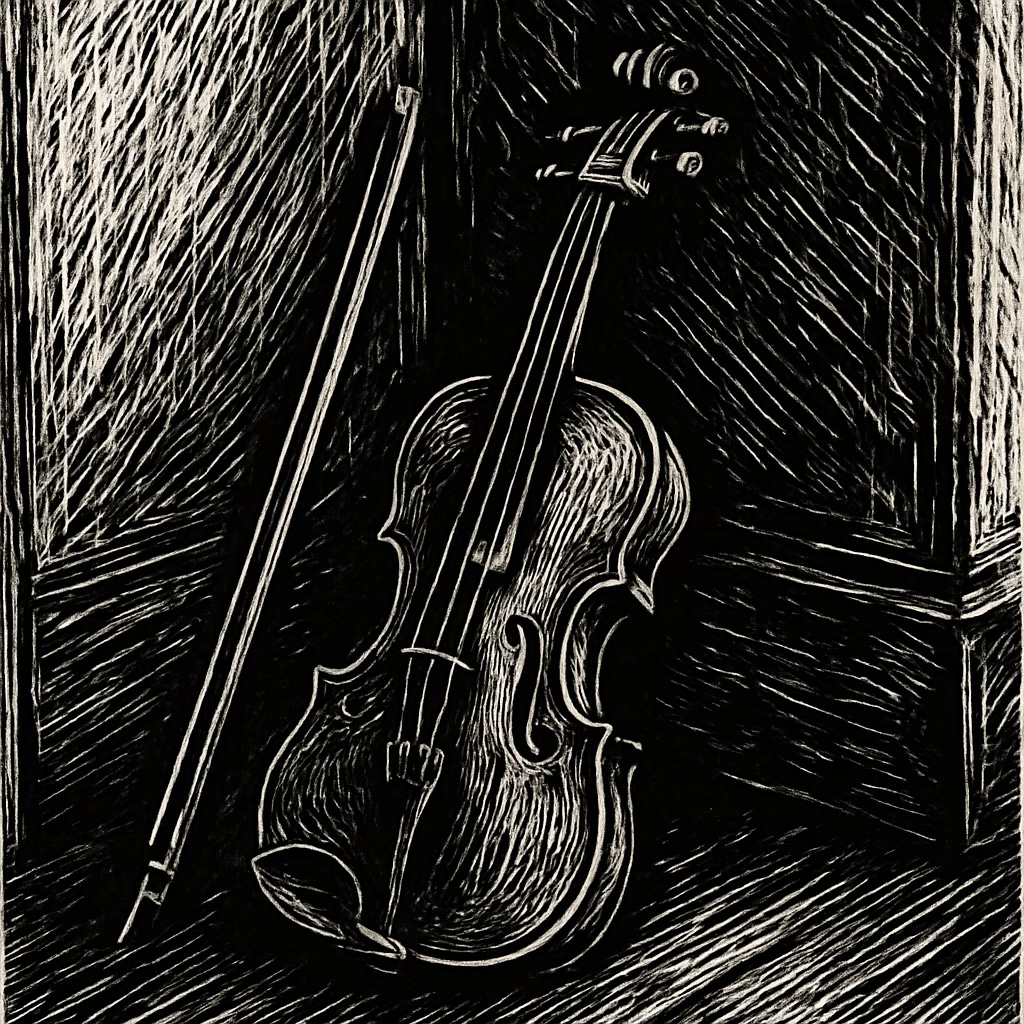

We must “have a capacity to receive, or even omnipotence can’t give,”2 echoes C. S. Lewis. The challenging work in the spiritual life is making ourselves ready to receive — to recognize God’s best gifts are less like being given a rare wine and more like receiving your first violin.

The pleasure we draw from the wine is wonderful, but once enjoyed, it is gone. The violin, however, is a far richer gift. If we give ourselves to it, if we train with it, if we listen to what it wants to tell us, it can deliver a deeper pleasure. It’s the kind of pleasure that never recedes, but grows stronger with use. The more we give to it, the more it gives to us. These are the best kind of gifts. The ones that draw us into themselves, and yet pull us out of ourselves. The ones we thought were for us alone and yet, over time, beg to be given away. This is virtue. This is goodness. And this is what God wants to give. If we’ll pursue it, if we’ll train for it—our hands will slowly open, the key will start to turn, the bud will begin to bloom.

Room to Reflect

George MacDonald says we “do not want the best.” In what areas of your life do you find yourself settling for less than God’s best?

C. S. Lewis reminds us we need “a capacity to receive.” What practices help open your heart to receive from God, and what habits might be closing you off?

How does this picture of virtue—as something to be pursued, practiced, and shared—reshape the way you think about goodness in your daily life?

MacDonald, George. Unspoken Sermons. United States: Cosimo, Incorporated, 2007, 207.

Lewis, C. S.. A Grief Observed. (United Kingdom: HarperCollins, 1994), 59.

Wonderful reflection, thank you.

I think immediately of the utter lack of silence in most of my daily life. Then, when there is a moment of quiet, it's difficult ... maybe even frightening? Because that silence is an invitation to experience reality and converse with God. Amazing how we resist that.